A MEETING OF FRIENDS AND FOES (OR AT LEAST RIVALS)

Well it is definitely not a G2. While the global financial crisis was raging and there was strong crisis management among the leading global powers, it appeared to many that the collaboration between China and the United States reflected the real prospect of a near condominium of global governance leadership. It was not true then; and it’s not true now.

Indeed, the US-China relationship remains riddled by questions. Can the two avoid the natural competition and conflicts that arise between rising powers (in this case, China) and traditional powers like the United States? History is filled with similar clashes and most experts saw ample evidence of those tensions in 2010: tensions around currency exchange-rates, the Korean Peninsula, the South China Sea, military sales to Taiwan, the breaking of military-to-military relations, intellectual property, Tibet and Chinese dissidents. Journalists have engaged in a virtual “horse race” with one another to find new signs of tension between China and the U.S. As Michael Wines and David Sanger, the Washington correspondent for the New York Times described the relationship in early December in “North Koreas Is Sign Chilled US-China Relations”, “The year has witnessed the longest period of tension between the two capitals in a decade. And if anything, both appear to hardening their positions.”

So what is the state of relations between these two and what can the Hu Jintao State visit to Washington do to alter or reinforce the bilateral relationship? There certainly is in Washington a strong “China Threat” school. This Washington view emphasizes the growing assertiveness of China’s leaders and officials and in particular suggests the growing China military presence. The “China Threat” school – including elements of the US military, of course – see a growing danger of confrontation between US and Chinese forces in the Pacific. Indeed the US military has suggested that the growing sophistication of Chinese weapons including anti-ship missiles, could force American naval forces farther and farther away from China’s shores.

A different view of the relationship is emerging in Beijing; what one might call the “China Can Just Say No” School. The view from this perspective focuses on China’s relative success in avoiding the global financial meltdown and the early return to rapid economic growth. This ‘School’ apparently concluded – as a result of the global financial crisis and the US struggle to return to economic growth – that China now had an opportunity to seize the global initiative. Washington watched with worry that China was becoming more assertive arose because proponents of this School saw the US in decline, and a China strong enough to say no to U.S. pressures. Washington fears that China will underestimate U.S. willingness to act on key strategic issues, and thus trigger a genuine crisis.

How then do we characterize the relationship? A number of US and Chinese experts have used the Chinese phrase – ‘fei di fei you’ (非敌非友)

neither friend nor foe – to capture the relationship. Such a view emphasizes the national interest component for both, and limits any vision of a truly collaborative relationship between the two giants. The concept of ‘neither friend nor foe’ deliberately squelches excessive optimism about the U.S.-China relationship in order to prevent dangerous disappointments and resentments in the international system. The view purports to be sober minded, and thus capable of maintaining competitive but stable relations.

In my view this characterization is useful but ultimately too pessimistic. As a result I believe that the relationship can better be described in Chinese as – ‘yi di, yi you’ (亦敌亦友) both friend and foe. This slight alteration of the Chinese phrase I believe better captures the bilateral relationship today. It also signals the possibilities for a collaborative and yet stable relationship. The phrase also avoids the kind of excessive optimism that may destabilize the relationship when officials try to characterize the relationship as cooperative. The perspective of “friend and foe” (or at least a rival) accepts that China and the United States will continue to compete – say over Taiwan – while also reflecting the countries opportunities to work together. Thus a China and the United States can work together on global macroeconomic imbalances though the two may not agree on policy options available. For global governance, the two may recognize that they can get beyond the rivalry and the growing military build-up – remembering that the United States still spends over $700 billion on the military versus a China that at the worst still spends say $120 to $150 billion – to work on issues that are in the national interest of both – stable global economy, restraint of nuclear proliferation and the maintenance of the nuclear non-proliferation regime (NPT) and climate change mitigation.

Yes the two are rivals, but the tight global interdependence and economic growth and well-being make them friends as well. So a meeting of the two Leaders can lead to announcements of cooperation in the global economy, energy and space. And just maybe the two can agree on principles of risk management reduction – finding the means to absorb and mitigate the consequences of difficult relations and discovering over time the way to cooperate in other areas of national interest extricating the relationship from a spiral of difficult rivalrous policies.

RELATED MATERIAL FOR THE WEEK OF JANUARY 17

BACKGROUND

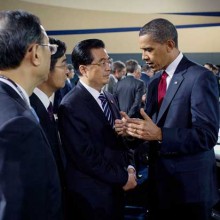

On January 19th, for the first time since 2006, President Hu Jintao of China will visit the United States on a State visit to Washington, D.C. President Hu has never visited Washington while Barack Obama has been in office.

President Hu and U.S President Barack Obama are expected to discuss issues related to US-Chinese affairs, including international trade and security. The security agenda for the state visit is likely to focus on North Korea, though there may also be discussion related to navigation rights in the South China sea. In addition to visiting Washington, President Hu and the Chinese delegation will tour Chinese-invested industrial factories and businesses in the United States in an effort to emphasize the positive impact of Chinese-American trade relations on the U.S economy.

In 1979, Chinese President Deng Xiaoping became the first Chinese leader to visit Washington and then-U.S President Jimmy Carter. Since then, Chinese leaders have visited Washington seven times. Two Chinese leaders, Premier Zhao Ziyang and President Li Xiannan, visited the U.S between 1979 and 1984. However, ties between the U.S and China deteriorated after the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident. The next state visit between the two states was delayed until 1997, when President Jiang Zemin visited Washington as well as a number of other American cities. President Hu himself has come to Washington once before, in 2006, on an “official visit” that was marked by tension and several awkward incidents.

In the weeks leading up to this State visit Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi visited Washington to discuss the upcoming State visit. U.S Defence Secretary Robert Gates visited China in an effort to rekindle US-Chinese military ties, almost a year after an American sale of arms to Taiwan led China to cut military ties with the United States. Just prior to Gates’ visit, photos of Chinese-made prototypes of stealth aircraft were leaked to the media, raising questions over the Chinese military’s willingness to collaborate.

The state visit is a new opportunity to improve relations. Generally 2010 has been viewed as a tense year of rising political, economic, and military tensions between the two powers. The visit is particularly significant as it is President Hu’s last, since he will be stepping down from office in 2012.

RELATED MATERIALS

- Xinhua features an exclusive interview with Henry Kissinger, whose secret visit to China in 1971 laid the groundwork for the normalization of US-Chinese foreign relations. Kissinger suggests that President Hu’s visit is “of fundamental importance in charting the future” of the relationship between the two states.

- On January 14th, U.S Secretary of State Hillary Clinton gave the inaugural Richard C. Holbrooke Address on the topic of US-China relations in the 21st century. Earlier, on January 6th, Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi gave a speech to the Council on Foreign Relations, which outlined the significance of President Hu’s state visit and the future of US-China relations.

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace holds a panel discussion on Hu Jintao’s upcoming visit to Washington as well as a site dedicated to the commentary and analysis on President Hu’s visit to Washington.

- Daniel Figer, Associate Director of the Columbia Law School, discusses what Hu Jintao’s visit can do for climate change in this blog entry.

- China’s CCTV interviews Mr. Gregory Yingien Tsang, their current affairs commentator, about his expectations on President Hu’s Washington visit.