THE G8 SUMMIT NOW ORBITS THE G20, AND THAT’S GOOD

With his usual hyperactive style, President Sarkozy has tried hard to burnish the reputation and enhance the purpose of the G8.

Even before the leaders and their advisors met in Deauville, a novel e-G8 was held in Paris under the theme of “The Internet; accelerating growth” – with a declared Summit theme “New World; New Ideas”. At Deauville itself, Sarkozy focused the summit on the Arab Spring — and how best to support the democratic transitions in Tunisia and Egypt.

Yet all of this gloss cannot hide the limitations that have grown around the G8 – the informal club made up of leaders from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, US, UK and the last Russia. At its peak in the 1980s, the summit benefited from a like-mindedness among its members. It may have lacked legitimacy as a self- appointed “club of the rich,” but members and non-members alike took the G7/8 seriously. Meeting at small sites, with a focused agenda, the G8 maintained a degree of control and influence on the global agenda.

Insiders from the G8 countries remain somewhat nostalgic about the old ways of doing things. Likemindedness allowed a comfort level among leaders and their advisors that is not easily reproduced in the new and enlarged G20 leaders’ summit created at the time of the 2008 global financial crisis. Going big is difficult. Consider the tensions over everything from big macroeconomic issues – like global economic imbalances — to the minutiae of global finance, like banking levie and reserve currency policy.

Altogether, the G8 leaders’ summits now work better as a caucus of wealthy democracies than as a steering committee of the global economy. Members of the G8 can work out disagreements at summits. They can use these meetings to test new policy ideas — like the need to improve international nuclear safety standards — or send policy signals to the rest of the world, like the Deauville message that “the global recovery is gaining strength and is becoming more self-sustained.” And the G8 can use its summits as a caucus to forge new partnerships with NGOs, like the Gates Foundation.

As a caucus, the G8 can rotate more explicitly around the orbit of the G20. And this is healthy. For all of the criticisms about the workings of the Muskoka/Toronto G8/20 summit process in 2010, this back-to-back model of summits will inevitably trump Sarkozy’s insistence on hosting the 2011 G8 at Deauville in May, and the 2011 G20 in November in Cannes.

The G20, for its part, will gain importance even as the expanded BRICS – Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – gains profile. <http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2011/0524_g8_summit_jones.aspx>. Unlike the UN and the International Financial Institutions, the G20 has been built on the premise of equality, without veto powers and differentiated votes and quotas.

Moreover, the feature that is overlooked by many US-based experts in the media and in the academies and think tanks, is the existence of a middle group of countries in the G20 that can create different forms of entrepreneurial and technical leadership. South Korea demonstrated this capacity by its ability to push a new notion of development onto the agenda in November 2010 at its summit in Seoul. Mexico in 2012 has an opportunity to reproduce this effort, as does Turkey and Australia in subsequent years. Although the BRICS has expanded, South Africa’s diplomacy is not always going to be in lock step with its bigger partners.

France has extraordinary diplomatic skills. Sarkozy was able to manipulate the G20 to enhance European representation from the outset of this leaders’ summit in November 2008. In Jean-David Levitte it has the most experienced Sherpa to help shape the agenda.

Yet the French attempt to push the Internet onto the G8 agenda has produced an assertive pushback. On ideological/policy grounds countries such as the UK have opposed the idea of a worldwide regulation of the web. So of course have the mainly US Internet executives who were invited to both the e-G8 and the G8 summit itself.

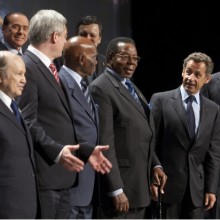

There are also major risks of the G8 putting the Arab Spring at the core of the G8 agenda. As the 2009 L’Aquila G8 summit revealed, inviting leaders in any ‘outreach’ process can backfire, as honored guests such as Hosni Mubarak, the then President of Egypt (who followed up his attendance at the Italian summit with a bilateral meeting with Sarkozy in Paris) and Colonel Gaddafi, the then undisputed leader of Libya (who at L’Aquila was greeted by a serving US president for the first time).

Nor can the G8 leaders in the aftermath of the financial crisis mobilize massive resources by themselves. To punctuate this point the efforts of the G8 in support of the Arab Spring (mostly in the form of debt relief and loan guarantees, albeit with a new role for the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development) was overshadowed by the plan of Qatar to create a Middle East Development Bank, another illustration of the growing influence of small as well as big emerging powers.

The advantages of retaining the G8 as a caucus need to be more openly discussed. This framework points away from a culture of over-promising and self-indulgence, with extensive communiqués on everything. What tangible promises emerge, often in fast response to an evolving situation, will have to be focused and subject to ongoing accountability measures. But the main concern of the G8, beyond its important symbolic attributes, will be coordination on an increasingly wider spectrum of issues with regard to the G20.

Although the G8 has proven to be a resilient body it is also one that will also need to adapt increasingly secondary role. As the Deauville summit confirms, it is no longer the main-game of global politics and policy.