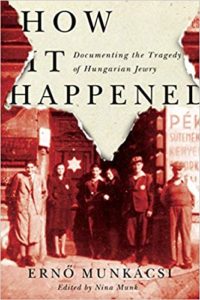

On December 4, 2018, the Hungarian Studies Program at the Munk School’s Centre for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies, in conjunction with the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies, will host a book launch for How It Happened: Documenting the Tragedy of Hungarian Jewry. Written by Ernő Munkácsi and translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel, the book is a detailed, first-hand account of the atrocities committed against Hungarian Jews during the Holocaust. We spoke with the book’s editor, journalist and author Nina Munk, about Munkácsi’s insights and the legacy of the Holocaust in Hungary.

Q: In the months following the Nazi occupation of Hungary in March 1944, 437,000 Jews were deported from Hungary. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, Hungarian Jews were the largest single group of victims. In the book’s preface, you state that to read How It Happened is to understand how the Budapest-based Judenrat (Central Jewish Council), an administrative body set up by the SS and Hungarian allies, “inadvertently facilitated the Nazis’ wholesale extermination of Hungarian Jews.” What was the Jewish Council and what role did it play in the context of the Holocaust?

A: The Central Jewish Council was established by Adolf Eichmann’s Sondereinsatzkommando immediately after the Nazis entered Hungary on 19 March 1944. The Jewish Council’s wretched job was to implement the regulations and orders of the German and Hungarian persecutors, a difficult, precarious job that forced them to carry out directives against their fellow Jews. Even today, the topic of the Jewish Council is highly contentious. The tragic role they played in Hungary, Poland, and other Nazi-occupied nations is often defined in terms of “impossible choices” or, to quote the Holocaust scholar Lawrence L. Langer, “choiceless choices.” The overwhelming question that Munkácsi aims to answer is why didn’t the Jewish Council do more to save the Jews of Hungary?

Q: Munkásci’s work was one of the first published histories of the Holocaust in Hungary. His account—at once personal and thoroughly documented—provides a unique glimpse into the “choiceless choices” faced by the Judenrat. In the wake of the Holocaust, many survivors felt that the Judenrat had failed to raise the alarm and that their chief strategy of “compliance and petitioning” amounted to complicity. How does Munkácsi’s account handle this dilemma?

A: In her biographical essay about Ernő Munkácsi, Susan Papp writes that by acting as secretary for the Jewish Council he surely believed he could act as a bulwark against the Nazis. The reality was something very different, of course, as revealed by a disquieting joke that Ernő recounts in How It Happened:

A Jew is woken up in the middle of the night by a banging on his door.

“Who’s there?” he calls out.

“The Gestapo,” comes the answer.

“Thank God,” says the Jew, with obvious relief. “I thought it was the Jewish Council!”

Many years later, in The Politics of Genocide, Randolph L. Braham would describe the Hungarian Jewish Council as naïve, ineffective and “almost completely oblivious of the inferno around it.” Hannah Arendt, Rudolf Vrba, and others echoed Braham’s criticism. In his book, Munkácsi tries to defend the Council. While acknowledging that they made poor decisions, he insists that they acted with the best of intentions. In his introduction to How It Happened, my colleague, Ferenc Laczó, approaches Munkácsi with pathos, arguing that while he may have been weak, he was also trapped by a lack of morally sound alternatives. Above all, as Ferenc Laczó argues, it’s critical that the Judenrat is not made into a scapegoat for the sins of others.

Q: Ernő Munkásci was your father’s first cousin (once removed), an influential member of the Hungarian Jewish elite and a member of the Judenrat. How has editing this book deepened your understanding of the Holocaust in Hungary and your own family’s story?

A: My father was lucky enough to escape Budapest in June 1944, as the cattle cars rolled from Hungary to Auschwitz at peak capacity, so I’ve been hearing about the Holocaust since I was a child. And yet, diving deeply into Munkácsi’s book made me realize how little I really knew about what happened in Hungary in 1944. It’s an astonishing story that has not received as much attention as it deserves. It’s also, for me, a story that has forced me to grapple with bigger, more existential questions. While more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered, 14 members of my immediate family, including my father, survived. The unspoken, unsavoury fact is that my family, like many other survivors, used its connections and money to escape the inferno, while others with less money and fewer connections were murdered.

Q: Why is it important to you that How It Happened be translated into English now? What sets this work apart from the other accounts of the Holocaust? Why is it worth reading?

A: Scholars of the Holocaust in Hungary have long been influenced by the original 1947 edition of Ernő Munkácsi’s book. But How It Happened is not only an important historical record of the Holocaust in Hungary; it is a riveting first-hand account of the atrocity that deserves to be appreciated by a wide audience. By translating the book into English — and by adding an introduction, a biographical essay about the author, extensive annotations, photographs, and maps — we aimed to make this rare eyewitness account of the “last chapter of the Holocaust” accessible to an entirely new generation.

Click here to order How It Happened online at McGill University Press.

About the Editor: Nina Munk, the editor of How It Happened, is a journalist and author. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and the New York Times Magazine, among other publications. Her most recent book is The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty (Doubleday). Visit ninamunk.com

How it Happened: Documenting the Tragedy of Hungarian Jewry, by Ernő Munkácsi, translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel, edited by Nina Munk (McGill-Queen’s, 2018). With an introduction by Ferenc Laczó, annotations by Ferenc Laczó and László Csosz, and a brief biography of Munkácsi by Susan Papp.