The Trudeau Centre Fellow in Peace, Conflict and Justice is for Political Science doctoral students at the University of Toronto who are conducting research in areas related to peace, conflict and justice. You can read about our three PCJ fellows here.

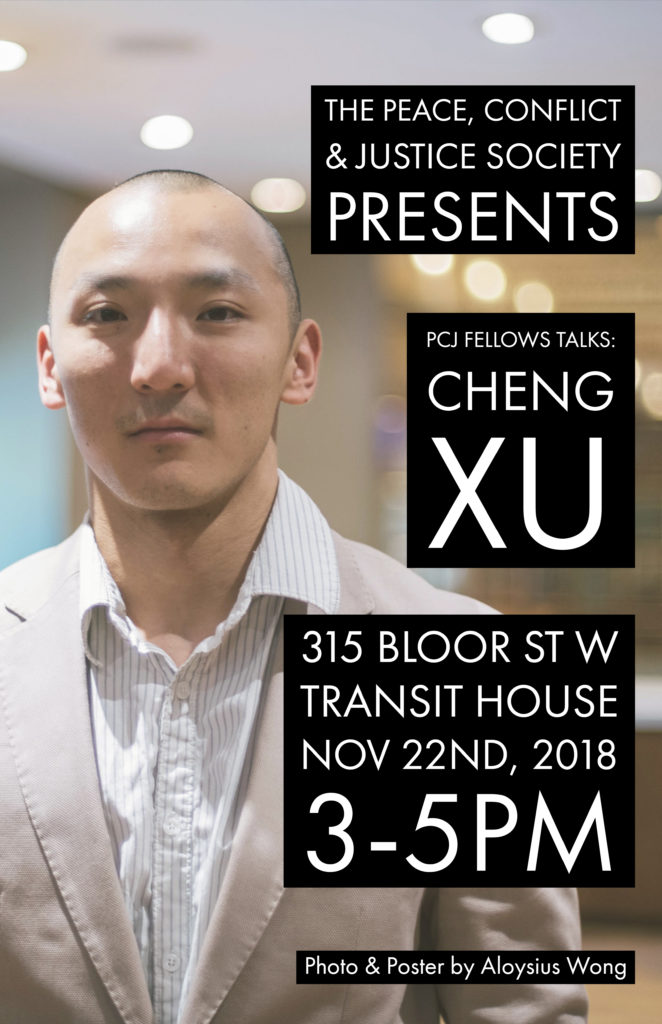

The recipients of this award become fellows of the Centre and have the opportunity to participate in its academic life. This includes presenting about their research at a ‘Trudeau Fellows Talk’ organized by the PCJ Society.

Cheng presented what others have described as “comparative politics gold”: two cases of ethno-linguistic groups with similar grievances around land against the Filipino government, with drastically different responses and results. His research compares the Filipino government’s response to Igorot tribes in the north and the Moro in the south. In particular, he illustrates the vignettes of the 2017 Siege of Marawi and the resistance to the Chico River Basin Dam Project.

Cheng began his presentation by providing some personal background, including a brief description of his time in the military. He outlined how he was motivated to pursue this research because he wanted to find a deeper answer to why a fellow Canadian—and family member of one of his soldiers—was kidnapped and killed by extremists in the Philippines. This, in part, drove his shift into academia and where he now seeks to complete his PhD in political science.

The first vignette he outlined was centred around the case in the southern Philippines, titled “A War of All Against All”. He described the case of the Moro people and their diversity, and how repeated moves by colonial powers and the government cost them more and more land. He explained how they were predominantly Muslim, a minority of 10% compared to the 90% Catholic population, concentrated in the southern part of the Philippines in the province of Mindanao.

The Siege of Marawi lasted five months—the longest urban battle in the Philippines’ modern history—during which a group of Islamic terrorists led by the Maute family took control of the city. It was characterized by violence and the displacement of tens of thousands of people, with the city in ruins by its end. This stood in stark contrast of the second vignette, set in the Cordillera: “Towards Perpetual Peace”.

What was fascinating in this second case is that the Indigenous resistance was largely successful. With leadership from the Kalinga tribe, they acquired more autonomy for themselves while stopping the dam project, and it was resolved more peacefully than in Mindanao. Violence was largely ratcheted down and compromises were created between Indigenous peoples and the government.

Cheng’s research seeks to further understanding of the causes of conflict in these cases and the methods towards peace as exemplified in the north. Aspects such as strategic interaction between insurgents, elites, and the government, he argues, are key to preventing violence. However, this is achieved differently depending on social relations and other factors between the aggrieved or insurgent groups and the government.

His supervisor, Aisha Ahmad, author of Jihad & Co. among others, was in attendance for part of the presentation. She left early but first emphasized to the room how proud she was of him and his research. I must concur. His research has given me a renewed hunger for knowledge, and I’m excited to witness where it will go next.