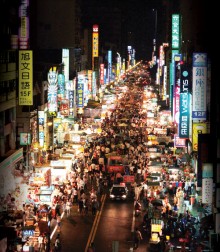

Author and professor Shelly Rigger wrote “America is boring at night” in her book titled “Why Taiwan Matters: Small Island, Global Powerhouse.” Why? Well, for one thing, night markets never flourished in America. Those who have had the fortune of experiencing the vibrancy and dynamism of Taiwanese night markets as I have would agree that the experience is jaw-dropping, from the bustling mood of the crowd, the chaotic chants of the merchants, and the narrow and crowded walkways, to the incredibly cheap and trendy merchandise that includes toys, makeup, clothing, accessories, and almost anything else you can imagine. And don’t forget about the food, which is undeniably the best representation of the local culture.

The night market is not a new phenomenon; it is a natural development from the vendors that cropped up on many street corners of ancient China. As early as the Tang Dynasty, night markets have been a part of local life in China. They usually took root along busy streets or at the foot of temples in response to local demand.

In Taiwan, the night market plays a central role in people’s lives. “Tonight we’re getting together and going to the night market. We’re putting on the latest fashions and applying our makeup. Everyone’s there: men and women, the old and the young. Lovers walk in pairs. Let’s stroll back and forth amid the hubbub. Stall after stall is packed with sweet-smelling delicacies. Let’s listen to the gracious owners make their sales pitches.” These are lyrics from “Strolling the Night Market,” a 1991 Taiwanese song from Zheng Jinyi. The song’s vivid depiction of the exciting scenery also reveals a local culture – a way of life embodied by the structure of the ancient phenomenon in its twenty-first century décor.

Fundamentally, the night market is a commercial and social complex at the grassroots level. Like regular street vendors in Taiwan, the market is essential to the local economy. According to a Taiwan-wide survey published by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), there were around 309,000 street vendors in Taiwan in 2008, 45,700 of which were night market vendors, and together, they earned NT$508.1 billion (CA$6.8 billion). The thriving numbers of these small businesses create much competition, which in turn makes the night market a fertile ground for innovation. Many famous Taiwanese xiaochi (snacks) originated from the streets of the night market.

Political scientist Stéphane Corcuff said that Taiwan is a conservatory and a laboratory of Chinese culture. He was right. In Taiwan today, although the bustling urban centre around it and the commodities traded within it are new, little has changed of the night market’s structure. It is a place to hang out and to relax after a day of work or school; it is a place for couples to go on dates; it is a place for tourists to experience the exotic local nightlife. Shuenn-Der Yu, an associate research fellow at the Academia Sinica’s Institute of Ethnology, comments on the social effects of the night market: “When people stroll night markets, their motivations aren’t just to eat snacks and shop. They also want to indulge in the special consumer pleasures and feelings that arise from being amid the noisy hubbub and chaos of crowds. People feed off the crowd’s energy.”

Yet somewhere in this cultural melting pot, an ancient Chinese culture has become hybridized and localized, mirroring Taiwan’s colonial past. Through experimentation and innovation, the night market has become the centre for localized creations. At first glance, the Taiwanese burger gua bao – a heavenly combination of braised pork belly, ground peanuts, sugar, and spices, stuffed inside a fluffy white Chinese bun – seems to be inspired by the American hamburger. Yet, if one is familiar with Chinese cultural food, it seem to better match the roujiamo, a similarly meaty sandwich containing pork and over twenty kinds of spices and seasonings, which originated in Shaanxi province, China. Taiwanese fruits are also famous for a reason. Through experimentation, a number of fruits and vegetables have emerged in new and better forms. Taiwan’s jujube is one such wonder. The original jujube was tiny and sour, and the skin was thick and marshy. After being adopted in Taiwan, it has become big and sweet, and the skin is now thin and crunchy.

Hence, the process of localization is an identity-constructing phenomenon. Echoing sociologist Erving Goffman and others, author Melissa Brown comments on the construction of identity in her book about Taiwanese culture: “Identity – a sense of who we are, in terms of how we fit into the world – is derived from how our minds process the world around us. Identities of individuals are socially constructed – formed and negotiated through everyday experiences and social interactions. Individuals understand these lived and social experiences in terms of the cultural meanings of the specific society in which they live.” Through the night market’s social and commercial platform, the local aroma is fused into the commodities and the experiences of visitors. Through the market’s social effects, unique cultural nuances are sown into the fertile soil of Taiwan’s localities, which simultaneously unifies the island culture through the stories that the night market vendors tell and sell.

Alan Ning is in his final year at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s College studying philosophy, political science, and classical studies.