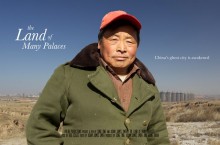

Picture this: A sprawling metropolis situated in the middle of a barren desert, comprised of a multitude rows of glimmering, but empty apartment blocks. Welcome to Ordos City. On January 16, 2015, The Asian Institute’s East Asia Seminar Series hosted a screening of The Land of Many Palaces followed by a discussion with the documentary’s director.

Directed and produced by award winning filmmakers Adam James Smith (Shangri-La, Role-Play) and Song Ting (Her Love Story), The Land of Many Palaces is a spectacular documentary that explores the lifestyle of Ordos City’s different inhabitants. Through following a Government Official’s journey as she mentors peasants on learning the basics of modern living, we witness how these migrant peasants adapt to this momentous change. Set in conjunction with the impact of Inner Mongolia’s growing resource extraction industries and infrastructural development, The Land of Many Palace offers a down-to-earth perspective of the city. It encompasses the sheer scale and magnitude of this ‘ghost town’, whilst focusing on the lives of individuals that became tied with the Chinese government’s drive to rapidly increase urbanization.

A relatively young city, the Ordos region transformed from a poor backwater to an economic powerhouse following the discovery of large reserves in coal. With incessant demands for more labor and residences for them to live in, the Chinese government decided to build an entire new city to accommodate such need. The spirit of this act is captured by the film through its dazzling cinematography. Large trucks carrying precious rocks are pictured against the backdrop of factories sending dizzying plumes into the once serene Mongolian sky, whilst metal pillars and barren concrete walls juxtaposed with the bright colorful billboards – predominantly in red hues – envisioning the future of this metropolis in construction. The enormity of the city itself is displayed by a wide panoramic sweep through the plaza center, with the stone chiseled statues of Genghis Khan and his compatriots gazing prominently with a socialist fashion. Public monuments dotted throughout the landscapes, with oddly shaped Museums and Sport Stadiums capturing the optimistic energy of its builders. Accompanied with sweeping, orchestral music, Ordos City looks like it jumped out straight from a science-fiction fantasy world.

The vastness of this city is met equally by the variety of its inhabitants. From the beginning of the film we are introduced to several urban dwellers, all of whom attempted to educate themselves to grasp the skill of city living. Hailing from different rural backgrounds, some of them are persuaded by their sons and daughters to live in the city, whilst others sold their land to the government in exchange for a new flat. From buying food produce in Supermarkets to using flushed toilet bowls, these former peasants have to conform to a ‘civilized’ lifestyle. This rhetoric of ‘civilization’ is endlessly emphasized by government authorities. Special package tours are arranged for newcomers to explore the city’s designated cultural spots (many of them recent constructions), talks and lectures are being held to introduce government policy and sell health insurances. Even social conduct and behavior are heavily emphasized during their orientation: with officials explicitly warn against spitting on the streets. Such regimen and complexity confounded and bewildered some of its new peasant movers. Some of them, forced to buy food at the supermarket instead of growing their own, is reminiscing the days of living off the land. Others were dismayed at the difference in reality as to their prospects, with a lack of suitable jobs to keep them busy.

Overall, the Land of Palaces is a visceral account of Chinese society itself. This Kaleidoscopic portrayal of the region’s civilians in response to the government’s arrangements stood in stark contrast to the atmospheric uniformity that it wishes to create. The socialist utopia that it wishes to create reflects their optimism to reach newer heights and achieve greater goals, whilst neglecting the strength of its shaky foundation through different means in order to materialize the ‘China Dream’.

-written by Arnold Yung, a second year student double majoring in contemporary Asian studies and history at the University of Toronto.

This article is part of a series of articles written by undergraduate students affiliated with the Asian Institute about events hosted by the Asian Institute.